The Seasons

"A journey through seasons" by Luiza Vizoli

Summer, autumn, winter, spring - words redolent of changing landscapes, of moving through time along a cyclical path. We wander through the seasons, says Itsik Manger in Tsi veystu ver der volkn iz? [Do you know who that cloud is?], and keep coming back, enhanced, to the same place:

... Fun vintn, velkhe kreytsn zikh | ... Of winds, that criss-cross somewhere afar |

The seasons1 in Yiddish and Ladino folksongs convey messages and feelings which are both descriptive and allegorical, as well as universal or culture-bound. Winter and fall are the dominant seasons in "Yiddishland" and thus feature in a significantly large number of songs. On the other hand, summer permeates Mediterranean landscapes, and it is no wonder that the Moorish lass, her skin turned brown by the summer sun, is a theme so prevalent in Ladino songs. I find it fascinating to saunter through these songs, season by season, and to discover how life in a particular environment affects the way we represent and understand our experiences.

Songs about the seasons express both textual and musical imagery. I thought it would be interesting to survey them against the background of images in famous paintings. I've been asking myself which messages can be conveyed by both pictures and songs. Also: what messages and feelings can songs convey that visuals can't? If that sounds too theoretical, I hope you simply enjoy both the paintings and the songs.

Summer

Summertime is when "the livin' is easy": Gershwin was said to have worried that this prelude to his quintessential "Black" opera sounded "too Yiddish"!2 There are a number of Yiddish translations3: how do you like this version of Zumertsayt? Summer is indeed a lazy time, as we see in Segalovich's ditty of a cat dreaming languidly on a roof: "Es iz gut a kotz zu zayn!" [How good it is to be a cat!]

"One summer day" is a phrase often used to set the scene and commencement of a story; it's hot, and people feel like venturing out. Songs in Yiddish and Ladino are no exception. An example in Ladino is the romansa Una tarde de verano 4: "one summer evening" a knight rides through the Moorish quarter and sees a Moorish girl laundering at a fountain. He wishes to marry her, but she turns out to be his sister. The Yiddish ballads Margaritkelekh [Daisies] and Gey ikh mir shpatsirn [As I go for a stroll] - both of which tell stories of boyfriends' cavalier behaviour - are also set in the summer.

A summer's night is often the setting for disappointed love: In a zumernakht tells of the heartbreak wrought by enlistment in the tsar's army; a similarly-titled song, In a sheyner zumernakht, tells of a lover's abandonment. And gypsies reading fortunes in a summer twilight set the scene for Manger's song of longing: Der zumer ovnt demert [The summer sun is setting].

Summer also represents the halcyon days of yore, hearkening back to an earlier period which is nostalgically remembered as calm and idyllic. We feel this in the song Zumerteg [Summer days], by Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman, who has often written songs about the seasons. (See Harbstlid [Autumn Song] and Friling [Spring], below). The soothing languor of a summer's day is recalled in Joseph Kerler's Yener langer zumertog [That long summer's day]. Most poignant is the function of summer in S'iz geven a zumertog [It was a summer's day], written by 18-year-old Rikle Glezer in the Vilna ghetto to the melody of Papirosn [Cigarettes]. Summer preceded the executions of Vilna Jews in Ponar, and also covered up the dreadful atrocities committed there.

There are hardly any songs in Ladino about the seasons. Nevertheless, the metaphor of the summer sun darkening the skin of a young girl permeates Spanish folksongs (see the discussion here) and has been carried over into several Sephardic songs, notably Morenica [Little dark girl] and Morena me llaman [I am called the dark girl].

Autumn

.jpg)

Autumn is traditionally associated with a sense of melancholy, as is exemplified in Manger's song Harbst [Autumn] with its relentlessly depressing list of images. Its chorus - "Shmerl with the violin, Berl with the bass; My eyes become moist when I hear the melody" - echoes that of a well-known folksong Tsen brider [Ten brothers], an allegorical tale of declining fortune.5 Just as bleak is Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger's Harbst, a dirge of blighted love.

However, Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman teaches us in Harbstlid [Autumn Song] to recognize what is valuable in seemingly unpromising circumstances: "Tsu vos-zhe darfstu vartn afn friling / as s'hot der osyen fule koyshns gold?" [Why do you need to wait for springtime, when autumn offers baskets full of gold?]

Zeitlin's miniature gem, Kleyner Harbst-Nign [Little Autumn Melody] describes the mystery of fiery gold. Leibu Levin's music and his rendition of the song is a meditation upon the cyclical return of the blazing tree in autumn. (Scroll beneath the video for the words and translation).

This website does not normally deal with Hebrew songs, but a particularly beautiful one which I'd like to mention - Stav Yehudi [Jewish Autumn] (video) - deals with a completely different aspect of autumn, the High Holy Days, which in Israel fall at the end of summer. It is the Hebrew term, Yamim Nora'im [Days of Awe], which is captured in the fearful, soul-searching and wistfully nostalgic words and melody.

Winter

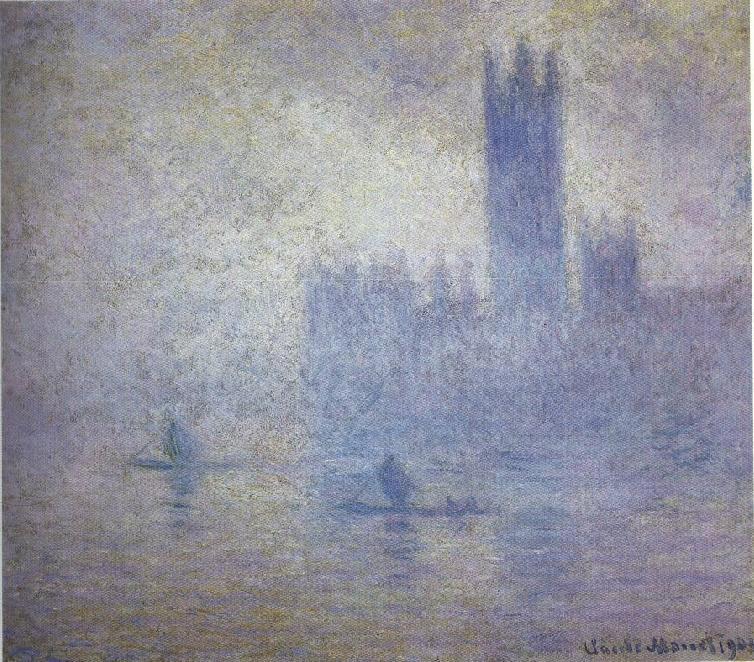

Monet's series of paintings of "Parliament House" in the winter fog has captivated me ever since I first saw them in the d'Orsay Museum of Paris. I'm in awe at the endless variations upon a single theme, both in real life and as captured by Monet's perceptive genius.

"Houses of Parliament, London" - Claude Monet (1840 - 1926)

Thinking of this infinite variety of shades and nuances, I wonder how many different things there are to say about the theme of winter. (Once again, this is a subject which is directly pertinent to the lives of Yiddish speakers, but not to Sephardic life). Winter in Europe means the vast whiteness of snow, bitter cold and biting wind, sickness and loneliness, having to stand in the frost to earn a paltry living. But winter also means the joy of skating on the ice, and songs about winter also talk about the cosy warmth of a fireplace.

Perhaps the most vivid portrayal of a small Jewish home in the lonely, endless, snow-covered fields of Russia is In vinter farnakhtn oyf rusishe felder [Russian fields on winter evenings], by David Hofshteyn. Although the song was written in 1912 (and published in 1919), Emil Gorevitz movingly interprets it from the point of view of "the martyred Yiddish poets of the Soviet Union"6 (1952). Similar imagery is employed in Di Lena [The River Lena], a poem by Abraham Liessin about a political prisoner exiled in Siberia.

There are many songs about the hardships of living in winter. The workers' song Hulyet, hulyet, beyze vintn [Howl, howl, raging winds], by Abraham Reisen, reflects the scenes of dire poverty in the winter of 1900.7 A moving picture of a destitute tailor suffering in the cold, Der kranker shnayder [The sick tailor], written by S. Ansky and popularized by singer Nekhama Lifshitz, ends with the words: "A shoyderlekhe kelt nemt on baym harts ... / As dos heyst lebn, vos iz toyt?" [A dreadful chill seizes one's heart ...: If this is living, then what is death?" Two very well-known songs are Papirosn [Cigarettes] and Bublitshki [Bagels], both about having to sell wares in the freezing cold.8 "Bublitshki" was written in 1926 in (Jewish underworld) Odessa to the tune of a popular foxtrot; a bowdlerized Yiddish version was popularized in the US by the Jewish-Swing Barry Sisters in the late '30's. "Papirosn" was written in Yiddish to the tune of a Jewish Romanian/Bulgarian song by Herman Yablokoff, who himself had peddled cigarettes during the German occupation of Grodno during WWI. From the time that the song was first broadcast in 1932, its harsh imagery has affected Jews in the US and all over the world. During the Holocaust, the words and music were adapted for two ghetto songs, including Si'z geven a zumertog, above.

Winter often signifies the end of a process, old age and dying. In Varshavsky's song, Der vinter [Winter] is personified as a grandfather coming to wreak misfortune in the homes of poverty-stricken Jews. In May ko mashme lon? [What is the meaning?], the rain beating upon the windowpane signifies not only the coming of winter for the impoverished Talmudic student, but also his stultifying life, "dying in this world and waiting for the hereafter". (Read this interesting discussion of the Talmudic phrase "may-ko mashme-lon" and of Abraham Reisen's poem). On the other hand, Sholem Aleichem's little pupil rebels against being cooped up learning the Torah: "Kh'vil nisht geyn in kheyder!" ["I don't want to go to kheyder!"] - He doesn't want to go and get beaten up by the teacher; he'd much rather be skating on the ice!

While winter ravages outside, a fire warms both body and heart within. The most beloved of all Jewish folksongs is Oyfn pripetshik [At the hearth], the more standard portrayal of a rabbi-teacher sitting by the fireside, teaching his beloved pupils the holy letters which will support them during the trials of Jewish life. Oyfn pripetshik is often sung as a lullaby; similarly, Unter beymer [Beneath trees], urges the child to sleep while winds rage outside. Another song about trees, set in the winter season, is Manger's Oyfn veg shteyt a boym, which tackles the metaphorical concept of treyst [comfort]. I'd finally like to mention a beautiful song by Vera and Emmanuel Hacken, Baym vinter fayer shteyen mir [We stand by the winter fire], in which a couple find comfort and rest in their old age.

Spring

The first painting most people associate with spring is Botticelli's Allegory - "Primavera". Spring universally stands for fecundity, birth and rebirth, and the imagery most often used is that of flowers and blossoms. However, as we see in the two paintings by Munch, a new spring season also conveys memories of the past, many of which are filled with sadness and loss.

"Primavera" is the word for "spring" in Ladino and other Romance languages. Primavera in Salonika describes the patrons of a Saloniki cafe listening languidly to Fortuna, a dark-eyed young girl, singing and playing the oud. The Abraham Masloum cafe actually functioned until the great fire of 1914 wiped out the Jewish Quarter, but there would have been many other cafes to service the thriving, cosmopolitan Salonikan Jewish community - until it was virtually annihilated in the Holocaust.

A song about spring in Ladino which relies heavily on symbolism is La rosa enflorese [The rose blooms] (also known as Los bilbilicos [The nightingales]): "The rose blooms in the month of May, [but] my soul darkens, suffering with love; The nightingales sing on the flowering tree, [but] beneath it sit those who suffer from love."

May is traditionally associated with spring, the first day of the month having been celebrated in pagan rites across the northern hemisphere since ancient times. For many Yiddish speakers, however, the first of May is International Workers' Day. May-lid [Song of May], popular in the US Workmen's Circle, speaks not only of fresh blossoms but of a new beginning and the end of slavery. This is reminiscent of Passover, our festival of new beginnings, which takes place in Nisan, the first calendar month of the Jewish year. Besides being the Jewish festival of spring [Chag ha'Aviv], Passover also represents the birth of Jewish nationhood following freedom from slavery in Egypt [Z'man Cheruteinu]. The animal symbolic of Pesach and, indeed, of the Jewish people as a whole, is the kid, whom we meet at the end of the Haggadah, in Chad Gadya [One only kid]. Itsik Manger has written a wonderful song - Dos lid funem tsigele [The song of the kid] - about freeing the kid from the yolk of "Chad Gadya" (representing the cold confines of Jewish tradition) and letting it spring freely about in the sunny fields.

A kid also features in the title of the children's song Tsigele-Migele [Little kid]: spring is the time when Daddy kisses Mummy and the children go dancing! Children's songs about spring - at least songs for children written by adults - are usually exuberant: examples are Kinder kumt, der friling ruft [Come children, spring is calling], by Mordkhe Rivesman, Di grine shnayderlekh [The wee green tailors], by Shike Driz, and Di friling iz gekumen, by Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman.

"Play and enjoy yourselves, children. Spring is here!" sings Gebirtig in Hulyet, hulyet, kinderlekh! [Frolic, rollick, children]. But this is not a children's song: it is sung by an old man who finds it hard to believe that life has passed so quickly. "Play on, play on, little ones while you are still young, For from spring will come forth winter in not so very long."9 In fact, most Yiddish songs, like La rosa enflorese, actually look back at spring with longing or regret. An example is "Az du bist do, iz friling do" [When you are here, spring is here], by B. Bergolts and S. Polonskii: these words of a mother holding her child are recalled through times of hardship.

One of the best-known songs of longing is Friling [Spring], written by Shmerke Kaczerginsky with music by Avrom Brudno. Kaczerginsky wrote the song in memory of his wife, who died in the Vilna ghetto. Spring enlivens the ghetto with warmth and flowers, but cannot bring back the poet's lost love.

The songs which Gebirtig composed during the Holocaust record the optimism, despair and nobility of our beloved song-writer. A zuniker shtral [A ray of the sun], written in the spring of 1941, is entirely optimistic: "Deliverance is coming to woods and fields, / For all of the birds, for mankind and the world / The song sought salvation is nigh." However, Undzer friling [Our springtime], written in the Krakow ghetto in 1942, is devoid of hope: "Springtime, it's already springtime ... The hangman is ploughing with his bloody sword / An enormous graveyard - the earth." One of Gebirtig's very last songs, Zun, zun, zang [Sun, sun, song], ostensibly a children's song, is an ode to spring which does not reflect any of the dreadful hardships that were being suffered at the time: "In the springtime of God's world, / See how lovely the sunshine is! / Field and woods with green are lit, / And the bird sings blissfully." Gebirtig did not compose music to the majority of his Holocaust poems: most of them, including the three spring songs mentioned here, were sensitively set to music, published and performed by a German composer, Manfred Lemm.10 Another poem of spring symbolizing the triumph of hope was written by Theresienstadt survivor Dagmar Hilarova in May, 1945: "The bitter years have passed by; / Springtime wind / The last sharp pain / Has swept away." Jerry Silverman has set the Czech words to an adaptation of Robert Schumann's Im wunderschönen monat May [In the wondrously beautiful month of May].

I'd like to end this section on spring with a song of renewed love: Friling, written and composed by Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman. "And you and I, like all around us / Refreshed and young again like the first flower / I saw the sparkle in your eyes / What a miracle has happened to you."

* * * * *

I think that Keats' sonnet "The Human Seasons" rings true for any culture and all "mortal nature". I hope you agree that it is an appropriate way to end this essay on "The Seasons" in Jewish songs.

"The Human Seasons"

John Keats (1795 - 1821)Four Seasons fill the measure of the year;

There are four seasons in the mind of man:

He has his lusty Spring, when fancy clear

Takes in all beauty with an easy span:

He has his Summer, when luxuriously

Spring's honied cud of youthful thought he loves

To ruminate, and by such dreaming high

Is nearest unto heaven: quiet coves

His soul has in its Autumn, when his wings

He furleth close; contented so to look

On mists in idleness—to let fair things

Pass by unheeded as a threshold brook.

He has his Winter too of pale misfeature,

Or else he would forego his mortal nature.

To finish off - finally! - on a joyous note, watch the Carmel A-Cappella quintet (from Israel) perform "Spring" from Vivaldi's "Four Seasons":

Notes and References

1 Note that the word "season" in English includes the meaning of "a time", which is the corresponding word favoured in Yiddish [tzayt] and Hebrew [et, z'man].

.jpg)

2 Gottlieb, Jack. (2004). Funny, It Doesn't Sound Jewish. SUNY Press. p.43.

3 Translations include one by Mendy Cahan in his disk "Yiddish Fever".

4 "Una tarde de verano" [One summer evening] is one of the many variants of the ballad "Don Bueso y su hermana" [Don Bueso and his sister]. Another variant is "Al pasar por Casablanca" [On the way to Casablanca].

5 A much happier use of this musician-motif is featured in Manger's song "Yidl mitn fidl" [Yidl with his fiddle]), and chances are that variously-named musicans playing their instruments "accompanied" other folksongs, too.

6 This is the name of the disk, featuring Emil Gorevitz with Zalmen Mlotek (piano).

7 Mlotek, E.G. & J. Pearls of Yiddish Song. Workmen's Circle.

8 Shternshis, A. Soviet and Kosher: Jewish Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. [Bublichki and Papirosn]

9 Most translations of the songs by Gebirtig on this page are by Hadassah Haskale.

10 Leichter, S. "Gebirtig's ghetto songs", in Anthology of Yiddish Folksongs, Vol.5 - Mordechai Gebirtig, pp.222-228.